Out of love, parents do so many things with their little baby to help their baby grow up and get ready for life, eventually for life on her own, with all the challenges that adult life will present. They feed, nurture, soothe, stimulate, teach and protect her. Researchers have long been interested in breaking down the great many different things parents do with their babies to find out which actions or patterns of actions may be most vital to the future resilience, security and healthy independence of the baby. Much work has gone into looking at parental sensitivity and responsiveness to the baby's needs. Recently, scientific focus is turning to the effects of maintaining skin-to-skin contact with one's baby in the formative months. Providing deliberate skin-to-skin contact has been done with premature babies since the 70's, where parents hold their babies skin-to-skin for several hours a day. This in part substitutes or compliments use of the incubators where the premature babies are normally kept. The practice developed out of a dire need in Columbia where there was a shortage of incubators, and lo and behold, the babies that were given plenty of skin to skin contact survived as well or better than the babies in the incubators. This discovery sparked 30 years of research into the mechanisms and effects of skin-to- skin contact. Over the years, the researchers established that skin-to-skin contact regulates the premature baby's physiological system and stabilizes temperature, heart rate and breathing. The premature baby also cries less, sleeps better and has less pain from medical procedures. Could it be that skin-to-skin contact has beneficial effects, not just on premature babies, but also on babies born at term and if the skin-to-skin contact was provided at a minimum in the first month following birth? And might these benefits be not just in terms of stabilizing the baby's physiological system? Could skin-to-skin contact perhaps benefit the baby's socio-emotional and cognitive development? And could it even benefit the mother as well? To investigate these questions, a group of researchers based in Nova Scotia, Canada enrolled approximately 100 mothers and their full term healthy babies, and randomly divided them into two groups. One group was asked to provide skin-to-skin contact to their babies, the other group (the control group) simply received no such instructions. As a result of these instructions, the skin-to-skin group maintained skin-to-skin contact for 5 hours a day in the first week and thereafter 3 hours a day until the baby was one month old. The control group provided little or no skin-to-skin contact. The skin-to-skin babies were held in the so-called frog position, naked apart from a diaper, chest-to-chest with the mother/father and with the legs spread out to both sides of the parent's stomach. This is the same position the baby is held in when carried in a well-designed ergonomic baby carrier. Beginning with the mothers, two significant effects emerged: The skin-to skin group of mothers suffered less from post-partum depression than the control group which had little or no skin-to-skin contact with their babies. And the skin-to-skin mothers maintained their original decision to breastfeed so that at three months, virtually all the skin-to-skin mothers who had initiated breastfeeding were still breastfeeding. This was in contrast to the control group where a sizable proportion gave up breastfeeding after three months, despite their original intention to continue. The babies in the study were young, up to three months old, so here the researchers had to utilize simple, yet powerful, measurements of their developing competencies. It is well-known that newborn babies use much of their available energy to adjust to life outside the womb and spend most of their time in what is called adjustment states, such as sleeping, drowsing, fussing or crying. But occasionally, the baby moves into a qualitatively different state, the quiet alert state. The quiet alert state is when the baby is awake and intently looking around. The baby has very little arm and leg movement. Only in the quiet alert phase can the baby take in information from the outside world. So the quiet alert state allows the baby to recognize its mother and father, get to know them, be aware of them and build up expectations for their parents. After only one week, there was a significant difference between the skin-to skin babies and those of the control group in the ability to stay in the quiet alert phase for an extended period of time. The skin- to-skin group therefore had more learning opportunities than the control group. Given the dramatically rapid development of a baby's brain, this would turn out to make a difference in the next test - The Still Face Task. The Still Face Task draws on the fact that even in its first few months the baby has developed expectations for the behavior of its caregivers through the repeated daily interactions. The Still Face Task has the mother/father placed in front of the seated baby within seeing and touching distance. The mother is instructed to play and interact as she normally would for a few minutes, and then follows a still-face episode, during which the mother does not respond to the infant while holding a neutral expression and finally a reunion episode, when the mother resumes interaction with her infant. At one month, the skin-to-skin babies demonstrated through their reactions to the still phase episode that they had developed expectations as to the mother's behavior, they became dissatisfied with their mother's still face and behavior and brightened up again in the reunion period. The control group had clearly not yet developed any such expectation. At three months, something startling appeared. The normal pattern of reactions of a three-month old baby to the Still Face Task is to be cheerful during the first playful period, to become distressed or gaze away in the still face episode, and then, in the reunion period, to gradually return to a more cheerful state. In this case the skin-to-skin babies increased the amount of positive vocalizations to their mother during the still face episode. They were clearly actively trying to re-engage their mothers by playfully calling to them. Why is this so startling? Normally even six month old babies do not increase their positive affect during the still face episode1 because it stresses the baby that the mother/father has suddenly turned unresponsive. This baby gazes away or frets or cries in an attempt to handle the stress that is building up within. At nine months babies have been registered to increase their positive vocalizations during the still face episode2. However generally not at three months. Seeing these findings in a greater context, three aspects of the baby's development are considered to be vital for resilience later in life: the capability to 1) regulate stress, 2) regulate attention and 3) interpret the state of mind of others. At three months, the skin-to-skin babies demonstrated an unusually advanced capability to overcome the stress of the Still Face episode by increasing their positive vocalizations instead of reducing them which would be the normal response to the stress inherent in the situation for a baby this young. A large review of the many scientific experiments with the Still Face Task has established a very robust link between higher positive affect in the Still Face episode and the quality of the baby's attachment at one year3. It appears that the brains of the skin-to-skin babies were being shaped to a future of secure attachment, good social competencies and a strong capability to handle stressful situations. This was brought about by the actions of the parents who provided their babies with generous skin-to-skin contact in the first month of the baby's life. Photography in this post is by Janae Kristen Photography Further Reading:

- The Nova Scotia Research Group has released a popular video, describing their findings. You can access this video via: http://www.mystfx.ca/InfantSkinToSkinContact

- Moore, GA, Cohn, JF and Campbell SB (2001). Infant affective responses to mother's still face at 6 months differentially predict externalizing and internalizing behaviors at 18 months. Developmental Psychology, 37 706-714

- Yato Y, Kawai M, Negayama K, Sogon S, Tomiwa K, Yamamoto H (2008). Infant responses to maternal still face at 4 and 9 months.Infant Behavior & Development 31 570–577

- Judi Mesman, Marinus H. van IJzendoorn and Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg (2009). The many faces of the Still-Face Paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Developmental Review Volume 29, Issue 2, June 2009, Pages 120-162

Emotional Benefits of Getting Outside

Spending time in nature with your baby can strengthen the bond between you. The simple act of holding your baby close, feeling their warmth, and sharing new experiences together can create strong emotional connections. It’s also a wonderful way to reduce stress and improve your mood. When my littles were extra fussy, I’d take a walk around the neighborhood. Even though I don't live in an area with trails and surrounded by nature, simply behind outside changed everything. A little vitamin D does wonders!

Cognitive Development

Nature is a sensory wonderland for babies. The different sights, sounds, and smells can stimulate your baby’s senses and promote cognitive development. Watching leaves rustle, hearing birds chirp, and feeling the texture of a tree bark can all contribute to their learning and development.

All About Baby Carriers for Nature Adventures

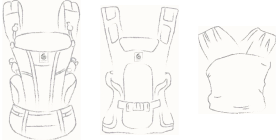

Choosing the Right Baby Carrier

When it comes to selecting the best baby carrier for summer adventures, there are several options to consider.

Types of Baby Carriers:

- Wraps: Perfect for newborns, providing a snug and secure fit.

- Slings: Ideal for quick and easy use, offering good ventilation.

- Soft Structured Carriers: Versatile and comfortable for both parent and baby, suitable for longer trips.

Factors to Consider:

- Baby’s Age and Weight: Ensure the carrier is appropriate for your baby’s size and weight. For example, Ergobaby’s Embrace Newborn Carrier is perfect for the fourth trimester where baby is small and you’re looking for an easy way to stay close. As they grow, you’ll want to upgrade to an all-position carrier that’s meant for growing babies.

- Parent’s Comfort and Ergonomics: Look for carriers with padded shoulder straps and lumbar support if you’re planning on longer outings.

- Ease of Use: Choose a carrier that is easy to put on and take off.

- Climate and Breathability: Opt for carriers made of breathable fabrics to keep you and your baby cool in hot weather.

Safety Tips:

- Proper Positioning: Ensure your baby is seated correctly, with their legs in an "M" position and their head should be close enough to kiss.

- Checking for Wear and Tear: Regularly inspect your carrier for any signs of damage.

- Ensuring Adequate Support: Make sure the carrier provides proper support for your baby’s head and neck.

Exploring Nature with a Baby Carrier

Ideal Spots for a Nature Walk with Baby

- Parks and Gardens: Great for leisurely walks and picnics.

- Nature Trails and Forests: Perfect for more adventurous outings.

- Beaches and Lakesides: Wonderful for enjoying the water and sand, with the right carrier.

Activity Ideas

- Hiking: Enjoy a scenic hike with a hiking baby carrier that offers support and storage.

- Bird Watching: Use your carrier to keep your baby close while you explore and observe wildlife.

- Picnics: A carrier can free up your hands, making it easier to carry picnic supplies.

Advantages of Using Strollers for Nature Adventures

While baby carriers are fantastic for mobility and closeness, depending on the adventure of choice you might want to be a stroller along too.

There are a LOT of baby stroller options on the market. So we understand how confusing it can be to choose the one that’s right for your family. Not only are there a variety of brands, but a variety of strollers that serve different purposes.

There are a few types of strollers on the market:

- Full-sized stroller: This is typically the stroller parents thing of buying for all its versatility.

- Lightweight or umbrella stroller:These compact strollers are perfect for on-the-go adventures.

- Jogging stroller: Designed for parents who want to combine fitness with outdoor adventures.

- Double stroller: Designed for parents with multiple kids, especially twins.

- Car seat carrier: These strollers connect to a specific car seat. We don't typically recommend these as they can be unsafe for baby and uncomfortable for parents who are pushing.

Learn more about the types of strollers and which one would be best for you.

Benefits of Bringing a Stroller

- Storage Space for Gear: Ample room for carrying all your essentials like a diaper bag, beach toys and more.

- Shade and Weather Protection: Built-in canopies to shield your baby from the sun when they are lounging.

- Options: If you have more than one kid, you can stroll with one and carry the other. Or, if you’re getting warm or your little one is getting fussy, you can switch up their position from stroller to carrier or vice versa.

Safety Tips for Strollers

- Ensure your stroller is in good working condition. Make sure buckles are still buckling and that there are no rips or holes that could compromise your baby’s safety.

- Use sunshades or bug nets to protect your little one’s skin.

- Securing the baby properly: always buckle up your baby for safety even if you think they are old enough to go without the buckle.

Combining Baby Carriers and Strollers

For the ultimate flexibility, consider using both a baby carrier and a stroller on your outings.

Combining both options allows you to adapt to different situations. Use the carrier for more rugged trails and switch to the stroller for smoother paths or when your baby needs a nap.

Transition Tips

- Smooth Transitions: Plan stops where you can easily switch from carrier to stroller.

- Pack Light: Only bring essentials to make transitions easier.

Tips for a Successful Adventure

Planning Ahead

- Route Planning: Choose baby-friendly trails and parks. Check local mom groups or outdoor groups and get recommendations for the best outings for kids.

- Check Weather Conditions: Avoid extreme heat or unpredictable weather. Even with our most breathable carriers, when it’s hot, it’s hot. And having two bodies against each other in the heat will be naturally hot and sticky already.

- Packing Checklist: Include diapers, snacks, water, sunscreen, and a first-aid kit. These all-position carriers have storage pockets where you can fit some of the items easily!

- Stay Hydrated and Nourished: Pack healthy snacks to keep energy levels up and bring plenty of water for both you and baby.

Summer adventures with your baby are a wonderful way to create lasting memories and enjoy the beauty of nature together. From baby carriers to strollers, Ergobaby products are designed to provide comfort and ease for both you and your little one. So, gear up, get outside, and explore the world with your baby by your side.

Ready to embark on your own summer adventures? Check out Ergobaby’s range of baby carriers and strollers to find the perfect match for your family’s needs. Visit our website today and start planning your next outdoor excursion!