One of the fundamental hopes most pregnant women have is the ability to easily breastfeed their baby. And for good reason because there are many health risks of not breastfeeding for both mother and child. For infants, not being breastfed is associated with an increased incidence of infections as well as elevated risks of childhood obesity, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, leukemia, and sudden infant death syndrome.

Why Breastfeeding Can Make a Difference

For mothers, there has been research suggesting that not breastfeeding is associated with an increased incidence of premenopausal breast cancer, ovarian cancer, retained gestational weight gain, type 2 diabetes, heart attacks, and the metabolic syndrome.

1

Furthermore, breastfeeding is very rewarding psychologically and enhances personal well-being. The world-renown oxytocin researcher Prof. Kerstin Uvnas Moberg was put on her pioneer track of researching the anti-stress properties of oxytocin by her own personal breastfeeding experiences.

2,3

There is a solid hormonal and physiological foundation for some women describing their breastfeeding experience as floating on an oxytocin pink cloud, with an unprecedented feeling of wellbeing. For women with an abuse history, being able to successfully breastfeed can be life-transforming.

4 It is truly awe-inspiring that the most fundamental tasks of life -- reproduction and nourishment of our children – can be delivered by the female body.

With these thoughts in mind, it is obviously a good idea for expectant mothers to prepare as best as possible. There are quite a few factors that impact each individual mother’s chances of success with breastfeeding. Some factors are beyond our control, but the majority can be influenced.

Baby Friendly Hospitals

If in any way possible in your area, choosing a hospital that has been certified as “Baby-Friendly” will improve your chances of getting off to a good start with breastfeeding. The Baby-Friendly Hospital designation requires that ten documented breastfeeding supportive measures are in place.

5

Childbirth complications have also been known to influence breastfeeding outcomes, so choosing a supportive practitioner, the optimum birth environment or hospital is another way to influence your breastfeeding outcomes. A coalition, consisting of national midwifery, lactation and neonatal/obstetric nursing organizations, has come together to define what they have labeled the “Mother-Friendly Childbirth Initiative”.

Similarly to the “Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative”, ten well-documented steps or measures govern birthing practices in designated hospitals. This initiative is relatively new, so few hospitals have obtained the designation this far, but you can use the

ten steps as your checklist when you search for your birth facility and inquire about their birthing practices.

In addition, attending a class, as well as mother to mother support groups provide guidance to help mothers learn what to expect, avoid problems and resolve issues, as well as know when to seek professional help before they become obstacles.

Even if you take these precautions, we still see that some mothers are off to a smooth start with breastfeeding, while others have met some unforeseen birthing circumstances that can influence their ability to breastfeed. What can a mother do to increase her chances of success in the face of early adversity?

How to Increase Chances of Breastfeeding Success

Engaging in extended physical contact could be a possible solution, as evidenced by a recent controlled research study, which sought to investigate

baby carriers as a potential and easily-accessible tool to increase breast feeding duration in normal, low-risk mothers.

6

The study supports the many individually reported experiences of improved breastfeeding outcomes from using a baby carrier, even in the face of non-optimum birth and postnatal care.

The study was carried out in Southern Italy, and included 200 middle-class mothers. For the mothers involved, regrettably, neither baby-friendly breastfeeding nor mother-friendly childbirth guidelines governed the practice of the hospital. More than 60% of the deliveries were made with cesarean sections.

Instead of keeping mother and baby together after birth or cesarean section, they were routinely separated and only re-introduced to one another after 3-6 hours. None of the mothers in the study had access to physical contact with their baby or to initiate breastfeeding within the first hour.

The 200 mothers were divided into two groups. Both of the groups had similar socio-economic and birth circumstances backgrounds. They both received information about breastfeeding and management of breastfeeding in the maternity ward.

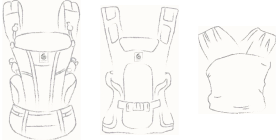

But one group (the “baby carrier group”) also received a baby carrier, designed for newborn use. In this group, each woman received a 30-minute instruction in the use of the carrier and was also encouraged to use it as often as possible, or at least 1 hour a day, during the first month after birth.

The researchers were particularly interested in measuring the rates of exclusive and of any breastfeeding at two and at five months of age, as well as the frequency of breastfeeding episodes during the first and the second month of life and the use of baby carriers during the first month of life.

One of the primary concerns of any researcher testing a new intervention or tool in a controlled study is how well the “intervention group” accepts the tool, and strict tabs are kept on this aspect, as it provides several important pieces of information. One is naturally whether the study participants are willing and able to use the suggested tool. Research also can provide information on why the tool did not work (as well as hoped for by the researchers…) for the participants. Furthermore, you can do a comparison of that subgroup in the intervention group, which did not use your tool as you had hoped for with your control group (who were not even offered the tool in the first place, hence their label as a control group).

What Researchers Found

The researchers found that out of the 100 mothers offered the carrier, 69 used it for more than one hour per day. Conversely, 31 mothers did not use the carrier. The reasons offered for not using the carrier included problems with cesarean section pain, the baby resisting the carrier by crying and the mother feeling uncomfortable with the carrier.

While breastfeeding rates were similar in the two groups at the discharge from the maternity ward, breastfeeding was significantly more likely among the mothers in the baby carrier group, both when measured at two months (74% vs. 51%), and at five months of age (48% vs. 24%). There were also significantly more mothers in the baby carrier group who fed their babies exclusively with breast milk at the two time-points (47% vs. 32% and 8% vs. 1%, respectively).

Among the 31 mothers of the baby carrier group, who did not use a baby carrier, breastfeeding rates were not different from those in the mothers of the control group.

When looking at the frequency of daily breastfeeding episodes, the mothers in the baby carrier group were found to be more likely to breastfeed their babies more than seven times during the day: 44% vs. 16% during the first month and 28% vs. 10% during the second month of life. More than 3 night feeds were also more likely in the mothers of the baby carrier group: 35% vs. 10% in the first month and 8% vs. 0% in the second month of life.

You may ask why the number of daily breastfeeding episodes is of interest to the researchers. One of the reasons is the relatively small stomach volume of newborns, which necessitates frequent feeds. The gradual increases in the baby’s stomach volume matches exactly the gradually longer sleep cycles of the baby in the first two months of life.

7 Failing to breastfeed in accordance with the natural physiological sleep and stomach emptying cycles of the baby could impair the child’s development.

Feeding on cue from the baby is the current formal recommendation from the lactation profession.

8 In addition, mother’s milk is digested quickly, often within 90 minutes of the last feeding, so rather than watching the clock, a mother should pay attention to baby’s cues, which is much easier if in close contact with the baby (e.g. baby in a carrier).

All the mothers who used their carrier were willing to recommend it to a friend, so they must have found the practice both pleasant and practical, and it helped them meet their breastfeeding goals.

In recent years, a new professional subspecialty of “babywearing consultancy” has developed. The babywearing consultants undergo theoretical and practical training of varying lengths, depending on which organization they are affiliated with.

The principal aim of babywearing consultants is to support mothers in their efforts to engage in carrying their babies, and they apply their experience and knowledge in helping the parents (ideally also including the father, and other caregivers, family or professional) finding the most suitable carrier(s) (there are now dozens of different options) and also overcoming individual difficulties in using the carrier, such as the ones described by the mothers in the study.

Working with a babywearing consultant or educator, as well as registering for a baby carrier prior to your child’s birth is a very worthwhile investment for your breastfeeding journey, and set you and your entire family off to a healthy, joyful and rewarding beginning, that includes short and long-term health benefits as well.

References:

- Stuebe A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):222-231.

- Uvnas-Moberg K. Oxytocin Factor: With a New Foreword: Tapping the Hormone of Calm, Love and Healing. 2nd edition. London: Pinter & Martin Ltd; 2011.

- Moberg KU. The Hormone of Closeness: The Role of Oxytocin in Relationships. Reprint edition. Pinter & Martin Ltd; 2013.

- Wood K, Van Esterik P. Infant feeding experiences of women who were sexually abused in childhood. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2010;56(4):e136-e141.

- Pike USNL of M 8600 R. THE GLOBAL CRITERIA FOR THE BFHI. World Health Organization; 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK153487/. Accessed December 13, 2017.

- Pisacane A, Continisio P, Filosa C, Tagliamonte V, Continisio GI. Use of baby carriers to increase breastfeeding duration among term infants: the effects of an educational intervention in Italy. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2012;101(10):e434-e438. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02758.x.

- Bergman NJ. Neonatal stomach volume and physiology suggest feeding at 1-h intervals. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2013;102(8):773-777. doi:10.1111/apa.12291.

- LLLI | Cue feeding: Wisdom and science. http://www.llli.org/ba/may99.html. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- Lauwers J. Counseling the Nursing Mother: a lactation consultant’s guide. 5th edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2011: 491.