“Baby carrying strengthens the bond between you and your baby.” This is a statement you often hear from baby carrying advocates, be it experienced mothers, babywearing consultants or midwives. It really only takes one look at a calm secure parent and her or his quiet, relaxed, content and alert baby in a good baby carrier to instinctively sense that this statement is probably quite true.

These are very fundamental questions: Should I give ample physical contact to my baby? Or, should I leave it more or less physically separated from me in the hope that this best fosters independence? For many parents, instincts and intuition are sufficient guidelines for their parenting choices. However, such instincts can be challenged by conflicting views, purported by some experts in the field. Some will argue that giving too much physical contact to a baby will make it clingy and dependent in the long run. One informational resource for such vital decisions comes from the field of science, in this case the science of child development. In a landmark study conducted in 1990, a team of researchers from Columbia University, New York, set out to explore this very question. The study was titled “Does Infant Carrying Promote Attachment?[1]” This study was designed to test the hypothesis that increased physical contact would promote greater maternal responsiveness and more secure attachment between infant and mother. Secure attachment has been found to correlate with autonomy and healthy independence. The research team was greatly inspired by the work of one of the absolute pioneers in the field of Attachment Theory, Mary D. Ainsworth. In her classic studies, in 1967, in Uganda and the United States, Ainsworth found that the amount of time mothers held their infants was related to the “security-of-attachment rating” that the infants received[2]. Mothers who, in the first months of life, held their infants for relatively long periods, and were tender and affectionate during the holding, had infants who, at 12 months of age, had developed secure relationships with them[3]. In contrast, if mothers were inept in handling their infants and provided them with unpleasant experiences during holding, the infants developed an anxious-ambivalent pattern of attachment. Several studies have found that mothers of avoidant infants had rejected or sought to minimize physical contact with their infants[4],[5],[6]. Thus, the research team argued, there is evidence that the amount and quality of physical contact between mother and infant is related to security of attachment. By increasing the quantity of physical contact, the experimental treatment of baby carrying may afford the mother opportunities to show affectionate and tender behavior, thus affecting the quality of interaction. The research team chose mothers from a low socio-economic background as participants for the study. These mothers were expected to have a range of social risk factors, which are likely to affect the quality of the attachment the mothers are able to form with their baby[7]. They would, therefore, also be the mothers most likely to gain from an intervention aimed at improving the attachment quality. If the mothers were already “good enough,” it would be hard to tell the difference – to establish if baby carrying improves the quality of attachment. After having given normal birth to a healthy child, the mothers were randomly assigned to either an experimental group that received baby carriers (more physical contact) or to a control group that received infant seats (less physical contact). The research team took careful precautions to rule out the risk that some mothers might already, prior to the onset of the study, be enthusiastic baby wearers. This could potentially confound the results. On the day after giving birth, the potential participants were read a list of different baby items and asked whether or not they would use each of the items if it were given to them as a gift. Embedded in the list were a soft structured baby carrier and an infant seat. Those who had already decided to use a baby carrier or who would not consider using one were eliminated from consideration. The study was explained in detail to those women who indicated that they were willing to use either a baby carrier or an infant seat. In order to obtain an objective estimate of the amount the soft baby carriers were used, pedometers were sewn inside them. Usage questionnaires administered during the test indicated that the mothers used the assigned “tools” frequently. At 3½ months of age, the babies were filmed during a play session with their mothers. The research team rated the mothers’ ability to respond to their babies’ vocalizations. This was achieved through detailed second-to-second analysis of the observed interactions. The mothers in the experimental (carrying) group were found to be more responsive than control mothers to their babies’ vocalizations. When the babies were 13 months old, the Ainsworth Strange Situation was administered[3]. This is a test which puts the infant through a series of increasingly (but mildly) stressful incidents, including brief separations from the mother, and being left alone with a stranger in an unfamiliar place. The baby’s specific pattern of response to the separations and reunions correlates to a specific pattern of attachment. The three patterns analyzed in the current study were the secure attachment, the anxious-avoidant attachment pattern and the anxious-ambivalent pattern. The secure attachment pattern denotes healthy autonomy and independence, accompanied by good social skills. The anxious-avoidant pattern makes the child appear independent, but regrettably with poor social skills and empathy and a latent tendency to display aggression. The anxious-ambivalent pattern results in a typical clingy and dependent child. The research team found that in the control group 38% of the babies were securely attached, and conversely, 62% insecurely attached. The majority of the insecure attached babies were anxious-avoidantly attached. In the experimental group 83% were securely attached, and only 17% insecurely attached. The function of having a control group in a scientific study is to inform what the outcome would have been if the intervention of baby carrying had not taken place. Evidently, a very significant change took place in the attachment between mother and child when mothers carried their babies, instead of adopting the more or less standard procedure of less physical contact. The researchers could conclude that when at-risk mothers carried their babies, carrying would indeed “strengthen the bond between mother and child.” Also, the nature of this bond was found to be healthy. Compared to other types of attachment-related interventions for at-risk mothers, the intervention of providing baby carriers turned out to be extraordinarily effective[8]. The research team speculated on the mechanisms that might be involved in the dramatic change of the mothers’ caregiving skills. Research in monkeys has demonstrated that mothers who have been exposed to maternal neglect in their own childhood tend to be negative towards their offspring, and, also, spontaneously reject physical contact. However, if exposed to sufficient amounts of physical contact with their offspring, their behavior would be modified.[9],[10] Research conducted in the decades following this study, indicate that the neurohormone oxytocin might be involved in the remarkable effect of baby carrying that the study brought to light. Some mothers have not had the most rewarding childhood or have been struggling with a difficult pregnancy and birth, perhaps combined with economic worries, high pressures of work or a fragile marriage. All these factors are known to put the strength and quality of the bond to one’s child at risk. Luckily, it does seem that the intuition that babywearing will strengthen that vital bond has been borne out by this careful study.

- Anisfeld E, Casper V, Nozyce M, Cunningham N. Does infant carrying promote attachment? An experimental study of the effects of increased physical contact on the development of attachment. Child Dev 1990;61:1617–1627

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of love. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mary D. Salter Ainsworth, MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E. & Wall S. Patterns of Attachment. A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. 1978 Hillsdale, New Jersey

- Egeland, B., & Farber, E. A. (1984). Infant-mother attachment: Factors related to its development and changes over time. Child Development, 55, 753-771.

- Main, M. (1977). Analysis of a peculiar form of reunion behavior seen in some day-care children: Its history and sequelae in children who are home-reared. In R. A. Webb (Ed.), Social development in childhood: Day-care programs and research (pp. 33—78). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Main, M., & Stadtman, J. (1981). Infant response to rejection of physical contact by the mother. American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 20, 292-307.

- Spieker, S. J., & Booth, G. L. (1988). Maternal antecedents of attachment quality. In J. Belsky & T. Nezworski (Eds.), Clinical implications of attachment (pp. 95-135). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ & Van Ijzendoorn MH. Promoting Positive Parenting. P. 74. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. 2008. ISBN 0-8058-6352-

- Harlow, H. F., & Suomi, S. J. (1971). Social recovery by isolation-reared monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68, 1534-1538.

- Suomi, S. J. (1973). Surrogate rehabilitation of monkeys reared in total social isolation. Journal of Child Psychology 6- Psychiatry, 14, 71-77.

Emotional Benefits of Getting Outside

Spending time in nature with your baby can strengthen the bond between you. The simple act of holding your baby close, feeling their warmth, and sharing new experiences together can create strong emotional connections. It’s also a wonderful way to reduce stress and improve your mood. When my littles were extra fussy, I’d take a walk around the neighborhood. Even though I don't live in an area with trails and surrounded by nature, simply behind outside changed everything. A little vitamin D does wonders!

Cognitive Development

Nature is a sensory wonderland for babies. The different sights, sounds, and smells can stimulate your baby’s senses and promote cognitive development. Watching leaves rustle, hearing birds chirp, and feeling the texture of a tree bark can all contribute to their learning and development.

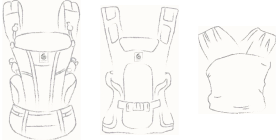

All About Baby Carriers for Nature Adventures

Choosing the Right Baby Carrier

When it comes to selecting the best baby carrier for summer adventures, there are several options to consider.

Types of Baby Carriers:

- Wraps: Perfect for newborns, providing a snug and secure fit.

- Slings: Ideal for quick and easy use, offering good ventilation.

- Soft Structured Carriers: Versatile and comfortable for both parent and baby, suitable for longer trips.

Factors to Consider:

- Baby’s Age and Weight: Ensure the carrier is appropriate for your baby’s size and weight. For example, Ergobaby’s Embrace Newborn Carrier is perfect for the fourth trimester where baby is small and you’re looking for an easy way to stay close. As they grow, you’ll want to upgrade to an all-position carrier that’s meant for growing babies.

- Parent’s Comfort and Ergonomics: Look for carriers with padded shoulder straps and lumbar support if you’re planning on longer outings.

- Ease of Use: Choose a carrier that is easy to put on and take off.

- Climate and Breathability: Opt for carriers made of breathable fabrics to keep you and your baby cool in hot weather.

Safety Tips:

- Proper Positioning: Ensure your baby is seated correctly, with their legs in an "M" position and their head should be close enough to kiss.

- Checking for Wear and Tear: Regularly inspect your carrier for any signs of damage.

- Ensuring Adequate Support: Make sure the carrier provides proper support for your baby’s head and neck.

Exploring Nature with a Baby Carrier

Ideal Spots for a Nature Walk with Baby

- Parks and Gardens: Great for leisurely walks and picnics.

- Nature Trails and Forests: Perfect for more adventurous outings.

- Beaches and Lakesides: Wonderful for enjoying the water and sand, with the right carrier.

Activity Ideas

- Hiking: Enjoy a scenic hike with a hiking baby carrier that offers support and storage.

- Bird Watching: Use your carrier to keep your baby close while you explore and observe wildlife.

- Picnics: A carrier can free up your hands, making it easier to carry picnic supplies.

Advantages of Using Strollers for Nature Adventures

While baby carriers are fantastic for mobility and closeness, depending on the adventure of choice you might want to be a stroller along too.

There are a LOT of baby stroller options on the market. So we understand how confusing it can be to choose the one that’s right for your family. Not only are there a variety of brands, but a variety of strollers that serve different purposes.

There are a few types of strollers on the market:

- Full-sized stroller: This is typically the stroller parents thing of buying for all its versatility.

- Lightweight or umbrella stroller:These compact strollers are perfect for on-the-go adventures.

- Jogging stroller: Designed for parents who want to combine fitness with outdoor adventures.

- Double stroller: Designed for parents with multiple kids, especially twins.

- Car seat carrier: These strollers connect to a specific car seat. We don't typically recommend these as they can be unsafe for baby and uncomfortable for parents who are pushing.

Learn more about the types of strollers and which one would be best for you.

Benefits of Bringing a Stroller

- Storage Space for Gear: Ample room for carrying all your essentials like a diaper bag, beach toys and more.

- Shade and Weather Protection: Built-in canopies to shield your baby from the sun when they are lounging.

- Options: If you have more than one kid, you can stroll with one and carry the other. Or, if you’re getting warm or your little one is getting fussy, you can switch up their position from stroller to carrier or vice versa.

Safety Tips for Strollers

- Ensure your stroller is in good working condition. Make sure buckles are still buckling and that there are no rips or holes that could compromise your baby’s safety.

- Use sunshades or bug nets to protect your little one’s skin.

- Securing the baby properly: always buckle up your baby for safety even if you think they are old enough to go without the buckle.

Combining Baby Carriers and Strollers

For the ultimate flexibility, consider using both a baby carrier and a stroller on your outings.

Combining both options allows you to adapt to different situations. Use the carrier for more rugged trails and switch to the stroller for smoother paths or when your baby needs a nap.

Transition Tips

- Smooth Transitions: Plan stops where you can easily switch from carrier to stroller.

- Pack Light: Only bring essentials to make transitions easier.

Tips for a Successful Adventure

Planning Ahead

- Route Planning: Choose baby-friendly trails and parks. Check local mom groups or outdoor groups and get recommendations for the best outings for kids.

- Check Weather Conditions: Avoid extreme heat or unpredictable weather. Even with our most breathable carriers, when it’s hot, it’s hot. And having two bodies against each other in the heat will be naturally hot and sticky already.

- Packing Checklist: Include diapers, snacks, water, sunscreen, and a first-aid kit. These all-position carriers have storage pockets where you can fit some of the items easily!

- Stay Hydrated and Nourished: Pack healthy snacks to keep energy levels up and bring plenty of water for both you and baby.

Summer adventures with your baby are a wonderful way to create lasting memories and enjoy the beauty of nature together. From baby carriers to strollers, Ergobaby products are designed to provide comfort and ease for both you and your little one. So, gear up, get outside, and explore the world with your baby by your side.

Ready to embark on your own summer adventures? Check out Ergobaby’s range of baby carriers and strollers to find the perfect match for your family’s needs. Visit our website today and start planning your next outdoor excursion!