“Attachment parenting,” as we know it, comes from the work of Dr. William Sears and his wife Martha Sears, R.N. They were among the leading proponents of attachment parenting in America. But the original idea comes from John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist, physician and writer. Born in 1907, he was raised by a nanny in his home, where he saw his mother only at exact times of the day, teatime for one hour. This was not uncommon at that time with the upper class. He was very attached to his nanny, but after 5 years, she had to leave. He was devastated, and, at age 7, he was sent away to boarding school. This was very difficult for him and he suffered tremendously. He was quoted in his book, Separation: Anxiety and Anger, as saying; "I wouldn't send a dog away to boarding school at age seven."[1] Because of his own experiences, he continued to have sensitivity towards children for his whole life. He did not consider boarding school a bad thing for children over the age of eight, or for any child who would be getting away from a difficult home environment. In fact, after World War 2, he saw it as a way for some children to create bonds that they might not have had the chance to create in their own homes. In 1949 The World Health Organization asked him to write a report based on his studies of the mental health of homeless children after the war. His article was entitled “Maternal Care and Mental Health.”[2] The result of this publication was that there was a widespread acceptance of his theory that “the infant and young child should experience a warm, intimate, and continuous relationship with his mother (or permanent mother substitute) in which both find satisfaction and enjoyment.” [3] He believed that without this intimacy, that there could be “significant and irreversible mental health consequences.” [4] This publication was influential in causing widespread changes in the amount and policies of institutional care for infants and children. John Bowlby’s work was a great influence on the work of Dr. and Martha Sears. In 2001, Dr. Sears wrote his book, The Attachment Parenting Book. This is when the term, the idea and the method really caught on in America. On their official website, he states: “Attachment parenting is a style of caring for your infant that brings out the best in the baby and the best in the parents. Attachment parenting implies first opening your mind and heart to the individual needs of your baby, and eventually you will develop the wisdom on how to make on-the-spot decisions on what works best for both you and your baby. A close attachment after birth and beyond allows the natural, biological attachment-promoting behaviors of the infant and the intuitive, biological, care giving qualities of the mother to come together. Both members of this biological pair get off to the right start at a time when the infant is most needy and the mother is most ready to nurture. Bonding is a series of steps in your lifelong growing together with your child.” [5] My personal experience with this method of parenting has convinced me of its efficacy. As I have written before, I had a difficult birth with my first child, and it left me feeling very vulnerable. Before her birth, I worked as a teacher. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go back to my job, but I had to go back to work part-time anyway. That idea ended up being thwarted by my little baby girl. Although I thought I had to go back to work, she had other plans for me. I arranged for her to be cared for by the best baby sitter in town, Jane Holiday. She was Mary Poppins incarnate; since we lived in England at the time, she even had the accent! She was a mother of two, a nurse and had had a private childcare business for years. I was only going to be teaching a few hours, three days a week. I thought that at 3 and half months, my daughter Morgaine would be fine. Think again. My daughter screamed from the minute I dropped her off until the minute I got back two hours later. We both (Jane and I) felt that she would do better the next time. Think again again! On the next date Morgaine screamed so loud and for so long, that Jane thought she might be having a hernia and took her to the village doctor. To this day, I believe, she was hoping for a tonic of some sort for herself. Needless to say, after this experience, I gave up on the idea of going back to work. I handed in my resignation and after a week of Dad taking care of her, Mom came back home. It was hard for us, and living extremely frugally wasn’t easy, but we made it work. I spent my days working, just not outside of our home. My baby was like the monkey I had met while visiting Thailand years before. She wrapped her arms and legs around me at all times. If she had had a tail she would have wrapped that too. There were times when I had to leave her crying in the arms of a friend that had amazing resilience to her cries. Luckily I had friends with earplugs. When she cried, she cried loudly! In the hospital, I had held my baby close to me from the moment she was born, and prided myself on the fact that I had never let her cry. The other, more experienced mothers on the ward would eat and smile at me indulgently as I ate my breakfast with her breastfeeding in my arms. They sat easily, eating their food, while their babies fussed and cried in their bassinets. I thought I was being a good mom at the time, but have realized since how a little alone time is necessary! In England, there is a funny ritual that still happens in the smaller hospitals. They encourage you to go out for a meal with your loved one(s) the night before you leave hospital to go home, sort of a last hurrah without baby. I did not want to go. I just wanted to stay with my new daughter. But my in-laws were there, and the nurses were shooing me out. With some coercion, I was talked into going out to dinner. When we returned we were met by a white-faced nurse, shaking her head back and forth, and saying, “You won’t sleep through her cries!” I should have known then, that this child wanted to be “attachment parented.” So, as I said, after giving up on going back to work at that time, I settled into a routine of feeding, holding, playing, holding, feeding, and holding for the next year. It was rough. There were times I wish I had a carrier that supported my aching back, but made due with a combination of holding her on my front, back and sides. (Sounds like a haircut!) After a while, her need to be carried around every minute stopped. Her desire to explore the whole wide world started and I was back to teaching part-time. Twenty-three years later I sit, with my daughter in the next room, while I write this article. She is packing her things to go back to Vermont, where she is living and working. This clingy, dependent baby has grown into an incredibly independent young woman. After her initial need to feel secure in the new environment called “life,” Morgaine has grown like a blossoming vine. She has travelled to many countries, volunteered in Peru, worked at outdoor adventure summer camps in Canada, and spent a year of college abroad in Florence, Italy. Now, she is the events coordinator at her alma mater, taking college students on adventurous excursions. This is the daughter, my monkey, who just wanted me to hold her until she was ready to fly. I’m glad I did.

References: 1 Bowlby, J. (1973). Separation: Anxiety & Anger. Attachment and Loss (vol. 2); (International psycho-analytical library no. 95). London: Hogarth Press. 2 Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal Care and Mental (Health.New York: Schocken.P.89). 3 Bowlby (1973) Separation: Anxiety & Anger 4 Bowlby 5 AskDrSears.com http://www.askdrsears.com/topics/attachment-parenting

Emotional Benefits of Getting Outside

Spending time in nature with your baby can strengthen the bond between you. The simple act of holding your baby close, feeling their warmth, and sharing new experiences together can create strong emotional connections. It’s also a wonderful way to reduce stress and improve your mood. When my littles were extra fussy, I’d take a walk around the neighborhood. Even though I don't live in an area with trails and surrounded by nature, simply behind outside changed everything. A little vitamin D does wonders!

Cognitive Development

Nature is a sensory wonderland for babies. The different sights, sounds, and smells can stimulate your baby’s senses and promote cognitive development. Watching leaves rustle, hearing birds chirp, and feeling the texture of a tree bark can all contribute to their learning and development.

All About Baby Carriers for Nature Adventures

Choosing the Right Baby Carrier

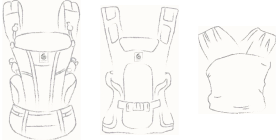

When it comes to selecting the best baby carrier for summer adventures, there are several options to consider.

Types of Baby Carriers:

- Wraps: Perfect for newborns, providing a snug and secure fit.

- Slings: Ideal for quick and easy use, offering good ventilation.

- Soft Structured Carriers: Versatile and comfortable for both parent and baby, suitable for longer trips.

Factors to Consider:

- Baby’s Age and Weight: Ensure the carrier is appropriate for your baby’s size and weight. For example, Ergobaby’s Embrace Newborn Carrier is perfect for the fourth trimester where baby is small and you’re looking for an easy way to stay close. As they grow, you’ll want to upgrade to an all-position carrier that’s meant for growing babies.

- Parent’s Comfort and Ergonomics: Look for carriers with padded shoulder straps and lumbar support if you’re planning on longer outings.

- Ease of Use: Choose a carrier that is easy to put on and take off.

- Climate and Breathability: Opt for carriers made of breathable fabrics to keep you and your baby cool in hot weather.

Safety Tips:

- Proper Positioning: Ensure your baby is seated correctly, with their legs in an "M" position and their head should be close enough to kiss.

- Checking for Wear and Tear: Regularly inspect your carrier for any signs of damage.

- Ensuring Adequate Support: Make sure the carrier provides proper support for your baby’s head and neck.

Exploring Nature with a Baby Carrier

Ideal Spots for a Nature Walk with Baby

- Parks and Gardens: Great for leisurely walks and picnics.

- Nature Trails and Forests: Perfect for more adventurous outings.

- Beaches and Lakesides: Wonderful for enjoying the water and sand, with the right carrier.

Activity Ideas

- Hiking: Enjoy a scenic hike with a hiking baby carrier that offers support and storage.

- Bird Watching: Use your carrier to keep your baby close while you explore and observe wildlife.

- Picnics: A carrier can free up your hands, making it easier to carry picnic supplies.

Advantages of Using Strollers for Nature Adventures

While baby carriers are fantastic for mobility and closeness, depending on the adventure of choice you might want to be a stroller along too.

There are a LOT of baby stroller options on the market. So we understand how confusing it can be to choose the one that’s right for your family. Not only are there a variety of brands, but a variety of strollers that serve different purposes.

There are a few types of strollers on the market:

- Full-sized stroller: This is typically the stroller parents thing of buying for all its versatility.

- Lightweight or umbrella stroller:These compact strollers are perfect for on-the-go adventures.

- Jogging stroller: Designed for parents who want to combine fitness with outdoor adventures.

- Double stroller: Designed for parents with multiple kids, especially twins.

- Car seat carrier: These strollers connect to a specific car seat. We don't typically recommend these as they can be unsafe for baby and uncomfortable for parents who are pushing.

Learn more about the types of strollers and which one would be best for you.

Benefits of Bringing a Stroller

- Storage Space for Gear: Ample room for carrying all your essentials like a diaper bag, beach toys and more.

- Shade and Weather Protection: Built-in canopies to shield your baby from the sun when they are lounging.

- Options: If you have more than one kid, you can stroll with one and carry the other. Or, if you’re getting warm or your little one is getting fussy, you can switch up their position from stroller to carrier or vice versa.

Safety Tips for Strollers

- Ensure your stroller is in good working condition. Make sure buckles are still buckling and that there are no rips or holes that could compromise your baby’s safety.

- Use sunshades or bug nets to protect your little one’s skin.

- Securing the baby properly: always buckle up your baby for safety even if you think they are old enough to go without the buckle.

Combining Baby Carriers and Strollers

For the ultimate flexibility, consider using both a baby carrier and a stroller on your outings.

Combining both options allows you to adapt to different situations. Use the carrier for more rugged trails and switch to the stroller for smoother paths or when your baby needs a nap.

Transition Tips

- Smooth Transitions: Plan stops where you can easily switch from carrier to stroller.

- Pack Light: Only bring essentials to make transitions easier.

Tips for a Successful Adventure

Planning Ahead

- Route Planning: Choose baby-friendly trails and parks. Check local mom groups or outdoor groups and get recommendations for the best outings for kids.

- Check Weather Conditions: Avoid extreme heat or unpredictable weather. Even with our most breathable carriers, when it’s hot, it’s hot. And having two bodies against each other in the heat will be naturally hot and sticky already.

- Packing Checklist: Include diapers, snacks, water, sunscreen, and a first-aid kit. These all-position carriers have storage pockets where you can fit some of the items easily!

- Stay Hydrated and Nourished: Pack healthy snacks to keep energy levels up and bring plenty of water for both you and baby.

Summer adventures with your baby are a wonderful way to create lasting memories and enjoy the beauty of nature together. From baby carriers to strollers, Ergobaby products are designed to provide comfort and ease for both you and your little one. So, gear up, get outside, and explore the world with your baby by your side.

Ready to embark on your own summer adventures? Check out Ergobaby’s range of baby carriers and strollers to find the perfect match for your family’s needs. Visit our website today and start planning your next outdoor excursion!