Touch has been called "the mother of the senses": perhaps because it was the first to develop in evolution. Touch is defined as "the most general of the bodily senses, diffused through all parts of the skin, but in humans, especially developed in the tips of the fingers and the lips." The fingers and lips have a disproportionately large number of neurons that travel to and from the brain. Thus they are the means by which the infant does most of its early learning; hence the need for “baby-proofing.” Touch is the earliest sensory system to develop. When a human embryo is less than an inch long and less than two months gestation, the skin is already highly developed. For example, when the palm is touched at two months gestation, the fingers grasp the palm. The fingers and thumb will close at three months when the palm is touched. Touch can have strong effects on our physiology. When the skin is touched, that stimulation is quickly transmitted to the brain, which in turn regulates our physiology. Different types of touch lead to different responses. Light pressure touch, for example, can lead to physiological arousal, and moderate pressure touch can be calming. Neonatal perception research by our group suggests that touch discrimination by mouth and by the hands is evident as early as the newborn period. Different texture nipples (nubby versus smooth), for example, can be discriminated by the newborn's mouth and by their hands. Affectionate touch Surprisingly, affectionate touch has rarely been studied in both the home and in infant daycare. Affectionate, stimulating and instrumental types of touch have been observed during natural care-giving and mother-child play sessions in the home. Maternal affection and stimulating touch decreased significantly during the second six months of life. This may relate to the infants’ accelerated gross motor development during the second half of the first year, namely crawling and walking, that would naturally move infants away from close physical contact with their mothers. Affectionate forms of touch such as hugging, kissing and stroking also decreased in infant daycare in later infancy and the toddler years. However, reciprocal communication increased in the second half-year of life and was predicted by the frequency of affectionate touch that occurred in the first half-year of life. Touch deprivation Infants and children in institutional care often receive minimal touching from caregivers, which is predictive of later cognitive and neurodevelopmental delays. The deprived children are often below average on cognitive skills when compared to same-age children who are raised in families. Unfortunately, in at least one study, this deprivation and the associated developmental delays persisted for many years after adoption. Touch deprivation has also occurred in infants of depressed mothers. For example, in one study, infants of depressed mothers versus those of nondepressed mothers spent more time touching themselves, which may have compensated for the less frequent positive touch from their mothers. They also showed more aggressive types of touching (i.e., grabbing, patting and pulling) than infants of nondepressed mothers during stressful situations, as if calming themselves. Massage Therapy Massage therapy has been noted to compensate for touch deprivation. Positive effects have been documented in many infant massage studies, especially for preterm infants who have gained significantly more weight and more bone density. In addition, following massage therapy, preterm infants have shown fewer stress behaviors, lower energy expenditure and enhanced neurological, psychomotor and sensorimotor development. A developmental follow-up at two years suggested that new preterm infants who received massage from their mothers had higher motor and mental development scores. In studies we have conducted we have shown increased vagal activity, gastric motility and IGF-1 (growth hormone) levels following massage of preterm infants, suggesting that these infants have been significantly calmed by the massage which may be the underlying mechanisms for the weight gain and improved development of the infants. Mothers of low birth weight infants have also helped reduce their infants’ developmental delays by massaging them. And, high-risk mothers, for example depressed mothers who massaged their infants showed more affectionate touch, and their infants were more responsive. The mothers benefited from massaging their infants and by their depression thus decreasing, and their infants’ growth and development also benefited. The mothers’ sensitivity and responsivity during interactions with their infants and the infants’ responsivity improved both in nondepressed and depressed mothers and their infants. These data demonstrate positive effects for the massager simply from giving the massages. These data were not surprising given that pressure receptors are also stimulated in the hands of the person providing the massage, and it is the stimulation of pressure receptors that mediates the positive effects of massage. Massage therapy has also been beneficial for normal full-term infants. In several studies infant irritability and sleep disturbances (the infancy problems most often presented to pediatricians) have been reduced. Massaging infants before sleep has been a more effective way to induce sleep than rocking infants. Massaging infants has also improved the interactions of mothers and infants. And, in a study on fathers massaging their infants, the fathers became more expressive and affectionate toward their infants Potential underlying mechanisms for infant massage effects Based on our comparisons between light and moderate pressure massage, we have suggested that the stimulation of pressure receptors by moderate pressure massage leads to enhanced vagal activity which in turn “slows down” physiology (e.g. slows heart rate) and stress hormone (cortisol) production. In turn, these massage effects would be expected to reduce pain syndromes, autoimmune conditions like asthma and diabetes and enhance immune function. For example, we have noted an increase in natural killer cells which kill bacterial, viral and cancer cells which would suggest less illness and disease for infants and young children. Summary Thus, touch is a critical sense for the development of infant perception and cognition. The parents’ affectionate touch helps the infant thrive and fosters the relationships between parents and infants. Touch deprivation, which is happening even in some of our infant nurseries, can lead to delayed development. Infant massage can compensate for the lack of touch. Infant massage has far-reaching effects. The use of moderate pressure massage (moving the skin) has contributed to weight gain and bone development in preterm infants and to less irritability and improved sleep in normal full-term infants. In China, parents learn to massage their infants from birth in the hospitals’ touch rooms. We might encourage all parents to learn infant massage and all nursery schools to have massage as part of their curriculum. In Sweden’s Peaceful Touch program all preschoolers receive backrubs as nursery rhymes are recited. Infant massage not only facilitates health and development, but also contributes to better parent-infant relationships. And, the massager benefits as much as the massagee.

Links: Liddle Kidz website, Nurturing Touch for the Growing Child: http://liddlekidz.com/tiffany-field.html

Emotional Benefits of Getting Outside

Spending time in nature with your baby can strengthen the bond between you. The simple act of holding your baby close, feeling their warmth, and sharing new experiences together can create strong emotional connections. It’s also a wonderful way to reduce stress and improve your mood. When my littles were extra fussy, I’d take a walk around the neighborhood. Even though I don't live in an area with trails and surrounded by nature, simply behind outside changed everything. A little vitamin D does wonders!

Cognitive Development

Nature is a sensory wonderland for babies. The different sights, sounds, and smells can stimulate your baby’s senses and promote cognitive development. Watching leaves rustle, hearing birds chirp, and feeling the texture of a tree bark can all contribute to their learning and development.

All About Baby Carriers for Nature Adventures

Choosing the Right Baby Carrier

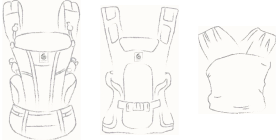

When it comes to selecting the best baby carrier for summer adventures, there are several options to consider.

Types of Baby Carriers:

- Wraps: Perfect for newborns, providing a snug and secure fit.

- Slings: Ideal for quick and easy use, offering good ventilation.

- Soft Structured Carriers: Versatile and comfortable for both parent and baby, suitable for longer trips.

Factors to Consider:

- Baby’s Age and Weight: Ensure the carrier is appropriate for your baby’s size and weight. For example, Ergobaby’s Embrace Newborn Carrier is perfect for the fourth trimester where baby is small and you’re looking for an easy way to stay close. As they grow, you’ll want to upgrade to an all-position carrier that’s meant for growing babies.

- Parent’s Comfort and Ergonomics: Look for carriers with padded shoulder straps and lumbar support if you’re planning on longer outings.

- Ease of Use: Choose a carrier that is easy to put on and take off.

- Climate and Breathability: Opt for carriers made of breathable fabrics to keep you and your baby cool in hot weather.

Safety Tips:

- Proper Positioning: Ensure your baby is seated correctly, with their legs in an "M" position and their head should be close enough to kiss.

- Checking for Wear and Tear: Regularly inspect your carrier for any signs of damage.

- Ensuring Adequate Support: Make sure the carrier provides proper support for your baby’s head and neck.

Exploring Nature with a Baby Carrier

Ideal Spots for a Nature Walk with Baby

- Parks and Gardens: Great for leisurely walks and picnics.

- Nature Trails and Forests: Perfect for more adventurous outings.

- Beaches and Lakesides: Wonderful for enjoying the water and sand, with the right carrier.

Activity Ideas

- Hiking: Enjoy a scenic hike with a hiking baby carrier that offers support and storage.

- Bird Watching: Use your carrier to keep your baby close while you explore and observe wildlife.

- Picnics: A carrier can free up your hands, making it easier to carry picnic supplies.

Advantages of Using Strollers for Nature Adventures

While baby carriers are fantastic for mobility and closeness, depending on the adventure of choice you might want to be a stroller along too.

There are a LOT of baby stroller options on the market. So we understand how confusing it can be to choose the one that’s right for your family. Not only are there a variety of brands, but a variety of strollers that serve different purposes.

There are a few types of strollers on the market:

- Full-sized stroller: This is typically the stroller parents thing of buying for all its versatility.

- Lightweight or umbrella stroller:These compact strollers are perfect for on-the-go adventures.

- Jogging stroller: Designed for parents who want to combine fitness with outdoor adventures.

- Double stroller: Designed for parents with multiple kids, especially twins.

- Car seat carrier: These strollers connect to a specific car seat. We don't typically recommend these as they can be unsafe for baby and uncomfortable for parents who are pushing.

Learn more about the types of strollers and which one would be best for you.

Benefits of Bringing a Stroller

- Storage Space for Gear: Ample room for carrying all your essentials like a diaper bag, beach toys and more.

- Shade and Weather Protection: Built-in canopies to shield your baby from the sun when they are lounging.

- Options: If you have more than one kid, you can stroll with one and carry the other. Or, if you’re getting warm or your little one is getting fussy, you can switch up their position from stroller to carrier or vice versa.

Safety Tips for Strollers

- Ensure your stroller is in good working condition. Make sure buckles are still buckling and that there are no rips or holes that could compromise your baby’s safety.

- Use sunshades or bug nets to protect your little one’s skin.

- Securing the baby properly: always buckle up your baby for safety even if you think they are old enough to go without the buckle.

Combining Baby Carriers and Strollers

For the ultimate flexibility, consider using both a baby carrier and a stroller on your outings.

Combining both options allows you to adapt to different situations. Use the carrier for more rugged trails and switch to the stroller for smoother paths or when your baby needs a nap.

Transition Tips

- Smooth Transitions: Plan stops where you can easily switch from carrier to stroller.

- Pack Light: Only bring essentials to make transitions easier.

Tips for a Successful Adventure

Planning Ahead

- Route Planning: Choose baby-friendly trails and parks. Check local mom groups or outdoor groups and get recommendations for the best outings for kids.

- Check Weather Conditions: Avoid extreme heat or unpredictable weather. Even with our most breathable carriers, when it’s hot, it’s hot. And having two bodies against each other in the heat will be naturally hot and sticky already.

- Packing Checklist: Include diapers, snacks, water, sunscreen, and a first-aid kit. These all-position carriers have storage pockets where you can fit some of the items easily!

- Stay Hydrated and Nourished: Pack healthy snacks to keep energy levels up and bring plenty of water for both you and baby.

Summer adventures with your baby are a wonderful way to create lasting memories and enjoy the beauty of nature together. From baby carriers to strollers, Ergobaby products are designed to provide comfort and ease for both you and your little one. So, gear up, get outside, and explore the world with your baby by your side.

Ready to embark on your own summer adventures? Check out Ergobaby’s range of baby carriers and strollers to find the perfect match for your family’s needs. Visit our website today and start planning your next outdoor excursion!